What role, if any, did religion play in the uprisings? How do the descriptions of religious rituals in the excerpts from Herard Dumesle’s Voyage to the North of Haiti and Antoine Dalmas’ History of the Revolution of Saint-Domingue demonstrate their authors’ perceptions of the Haitian Revolution?

In the primary source documents for Wednesday, religion is mostly prominent in the first two documents by Dumesle and Dalmas, which focus on the uprising in August 1791. Overall, it does not play a substantial role in the debates and situations that follow, which primarily emphasize the concept of liberty without mentioning religious ideas or themes. Dumesle’s excerpt (despite its fictional elements) highlights the importance of the Bois-Caiman ceremony, noting its centrality to the entire uprising when he writes that the slaves “formed a plan for a vast insurrection, which they sanctified through a religious ceremony” (Dumesle 87). In the speech that was supposedly given by one of the slaves, the influence of religion is especially clear. God is explicitly referenced toward the end of the speech, referred to as a supporter of the slave revolt: “‘But that God who is so good orders us to vengeance; / He will direct our hands, and give us help, / Throw away the image of the God of the whites who thirsts for our tears, / Listen to the liberty that speaks in all our hearts'” (Dumesle 88). Ultimately, Dumesle portrays the uprising as being motivated by a sort of religious fervor, associated with God as well as the concepts of liberty and vengeance (Dumesle 88). Describing the insurrection as “the most sad of spectacles,” Dumesle ultimately casts it in a negative light (Dumesle 88).

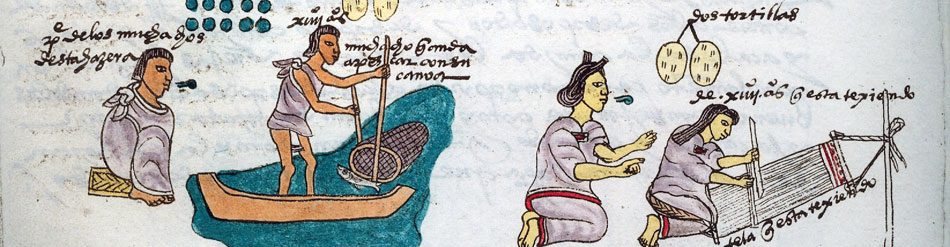

Dalmas describes the August 1791 rebellion and, more specifically, the Bois-Caiman ceremony, in an even worse light than Dumesle. For example, he states that “a black pig… was offered as a sacrifice to the all-powerful spirit of the black race. The religious ceremony in which the negres slit its throat, the greed with which they drank its blood, the importance they attached to owning some of its bristles which they believed would make them invincible reveal the characteristics of the Africans. It is natural that a caste this ignorant and stupid would begin the most horrible attacks with the superstitious rites of an absurd and bloodthirsty religion” (Dalmas 90). He condemns the entire revolt and its religious aspects, viewing the slaves as inferior while also associating their religious rituals with the violent nature of the rebellion.