I think one potential research question that I would possibly like to follow is how the colonization of Latin America changed the environment. I think this is important to study because this time period of colonialism is when environments started to change and really be disturbed by humans. I know that many of the indigenous empires did farm and cultivate the lands, so I am also curious about how the Europeans changed the way that the native people used land. We also know that because of the die-off of millions of people during this time caused the land to be reclaimed by forests and cooled the atmosphere. I am excited to learn more about different environmental changes.

Research Question

I am interested in ancient trade networks within prehispanic Mesoamerica. A question I might want to investigate is: how did the interconnectedness or disconnectedness of trade affect relations between ancient Aztec and Mayan society?

As a comparative project, I think it would be interesting to look at the ways trade remained central or expanded outside the boundaries of different Mesoamerican societies. One academic journal I was looking at discussed the importance of the marketplace because it was the center of commerce within a city. This allowed communities to come together and sell their products to other individuals from other regions. Another historical journal emphasized how dynamic the Mesoamerican economy was, which counters previous research that said that Mesoamerican economies were completely localized. There are many directions I could take this. I could focus specifically on certain resources, such as maize, obsidian, or crafts. Or I could look at the bigger picture and address the trade networks and trends between different Mesoamerican societies.

Potential Research Question (First Idea)

One of the research avenues I am toying with pursuing is to review colonial Latin American conquest dramas such as The End of Atau Wallpa and The Loa for the Auto Sacramental of The Divine Narcissus. How do these conquest dramas express the attitudes of the native peoples toward colonization, and how do those performative reflections stack up to primary documents detailing those same attitudes?

In my major, it is important to recognize the importance of pieces of drama from parts of the world that are not Europe. And further, in recognizing those records as historically relevant, they are made all the more important in academia; we should study the texts in the same ways as we study Shakespeare.

Potential Research Question

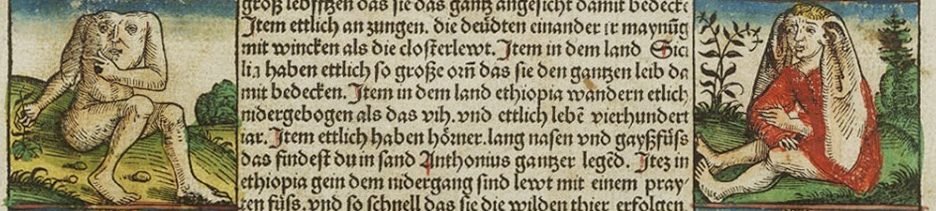

One potential research question I am interested in is as follows: What were the primary modes of thought in the late Middle Ages and how were non-European peoples and places described in literature?

This question is important because it allows us to learn about the worldview of Europeans in the Middle Ages, how they perceived the world around them, and how this perspective may have developed or changed over time. Furthermore, it can help us to identify the preconceived notions that Europeans had about the New World pre-contact. I think that, by looking at European modes of thought, we can better comprehend why they took certain actions and believed certain things about the world beyond Europe. It is also important to know what ideas people chose to write down versus those that they decided not to mention. Ultimately, all of these concepts may allow us to more easily track the European mindset, beliefs, and intentions post-contact.

More on Inca Architecture

By popular request, here is some more information on Inca masonry and architecture. The first is a quick, popular overview from the Ancient History Encyclopedia that describes Inca use of stones and bronze tools to shape rock.

I also found an older academic article on “Inca Stonemasonry” from Scientific American by University of California architect Jean-Pierre Protzen. In the article, he gives a summary of the historiography of Inca technologies, and then goes on to describe his efforts to recreate Inca wall construction. He provides a wealth of detail on the rocks used, quarries, and the tools used for transportation and structure.

As I mentioned in class, this is a topic rife with sophisticated-looking, poorly researched pseudo-scholarship. I found an example (I won’t link to it) of a youtube video with over 900k views claiming that the Inca build their walls with bags of concrete…. historians beware!

Lecture by Distinguished Historian on Women and War on Tuesday 9/10 @4pm

Please join us for the inaugural Hayden Schilling Lecture, a talk by the distinguished historian, Susan Grayzel, on women’s experience in the First World War. The event, open to the public, will take place on Tuesday, September 10 at 4:00 pm in the Lean Lecture Room.

Grayzel is Professor of History at Utah State University, having previously served as Director of the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies at the University of Mississippi. She is the author of several award-winning works, including War: Gender, Motherhood, and Politics in Britain and France during the First World War (1999) and At Home and Under Fire: Air Raids & Culture in Britain from the Great War to the Blitz (2012). She will also be leading a faculty workshop and meeting with students.

This talk is the first of what will be an annual event, The Hayden Schilling Lecture, supported by the Hayden Schilling Fund for History.

More details below. We hope to see you there! Greg Shaya, History

Public Lecture

Susan R. Grayzel, Utah State University

The Hayden Schilling Lecture: “Did Women Have a Great War? Reflections on Women’s Experiences 100 Years On”

Tuesday, September 10, 4:00 pm, Lean Lecture Room

This talk explores some of the ways in which women experienced the First World War in order to ask if women’s “had a great war.” It examines not only what women across a range of backgrounds and circumstances did during the war—where, how, and why they participated and what they thought about this—but as important, what a focus on women might add to our understanding of the First World War itself.

Meeting with Prof. Grayzel

Prof. Grayzel will be available to meet with students during the day on Tuesday, September 10. If you are interested in meeting with Prof. Grayzel – perhaps if you are working on topics of British history, gender history, war and gender – please contact Greg Shaya in the Department of History (gshaya@wooster.edu).

Short Biography

Susan R. Grayzel joined the faculty at Utah State University in 2017, teaching classes in modern European history, gender and women’s history, and the history of total war, having previously been Professor of History at the University of Mississippi, where she was also Director of the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies. Her most recent publications include Gender and the Great War (Oxford University Press, 2017), co-edited with Tammy M. Proctor. Her previous books include Women’s Identities at War: Gender, Motherhood and Politics in Britain and France during the First World War (1999) and At Home and Under Fire: Air Raids & Culture in Britain from the Great War to the Blitz (2012). She is engaged in two current research projects; one tracing how the civilian gas mask came to embody efforts to address the consequences of chemical warfare in the British empire, c. 1915-45, and the second with Prof. Lucy Noakes (University of Essex) on gender, citizenship, and civil defense in twentieth-century Britain. She is spending the academic year 2019-20, first as a visiting fellow at All Souls College (Oxford) for Michaelmas term 2019 and then as UK Fulbright Distinguished Chair at the University of Leeds from mid-January to mid-July 2020.

What I Want to Learn This Semester

A big part of the American experience is saying who is a true native in the area, with Latin American history is a huge argument torse what communities have been there the longest. With recent studies showing that most communities in the Latin American citizens of recent days are descendants of the original ancestors that lived in the colonial Americas. The biggest population traveled from north Siberia through the land bridge that connected Siberia and Alaska between about 34,000 and 11,000 years ago.

Learning the history of where the true ancestors would create and open mind that no one is truly a native in the land. This would make more of an idea that we are all immigrants and that everyone should be equal. It would help with the acceptance of immigration moving to different countries. While also learning the process of finding proof of the original tribes located in Latin America. With also showing what was truly their experience they had with the Europeans traveling over. With the allegations torse of Columbus that truly made showed that the Europeans did not come to make things better and took advantage of people that different than them. Which shows that this is a constant problem in all of history.

Class Notes 9/4

In today’s class, we focused primarily on Mesoamerica, the Aztecs, the Mayan people, and the question of gender in engraved stone tablets. For clarification, professor Holt explained how the Mayan empire peaked from 250-900 A.D. and then collapsed in the 900s. The Aztecs were people from Atzlan, which made up what is now the central and southwestern United States. The Mexica, or Aztecs, were the powerful ethnic group in Mesoamerica at the time when the Europeans entered the picture. We also talked about Tenochtitlan, which Schwartz and Seijas called a “world-class metropolis” (5). Near the end of the class, Katrina gave a presentation on the book Gender and Power in Prehispanic Mesoamerica. She touched on how the author emphasized features in Mesoamerican artwork to enhance her argument. The author argued that European interpretations of these artifacts were incorrect and that the images were far more complicated and had a lot to do with the position of women in society. How did the Spanish conquistadors view Tenochtitlan when they first discovered it? What role did women play in society judging by their presentation on Aztec stone carvings? Was Tenochtitlan the economic center of Mesoamerica? The readings, for the most part, described the complexities of Mesoamerica society in depth. However, I found the statistics to be a bit offputting. In LA&P, Tenochtitlan had a population of 150,000. But in Victors and Vanquished, the population was estimated at 300,000. Which one was accurate I am not sure. Does this possibly refer to 150,000 people living within the city limits, or does it include the surrounding area as well?

Note from KH: There is often a considerable range in calculating historical population figures. It makes sense if you think about what kinds of governments would value detailed records of individual residents (versus tracking community contributions to the empire, or other things) and also what kinds of surviving evidence we’re drawing on for understanding Tenochtitlan in 1519. Scientists use different methods for these calculations when we can’t rely on an accurate, detailed population count. Science magazine has a brief article here about statistical models archeologists can use to estimate population.

Something we talked about at the end of class was The Aztec Stone of The Five Eras. This stone tablet illustrates how advanced Aztec society was, especially regarding astronomy, their interpretations of time, seasonal changes, and their subjecthood to deities. On page 25 and 26, the author refers to the way the stone tablet “points to Tenochtitlan as the spatial center of authority,” and how the Aztecs were intuned with environmental calamities and prosperity. At the center of the turmoil and prosperity was the metropolis, Tenochtitlan.

Nahuatl- the ancient language spoken by the Nahua people in Mexico and El Salvador

Nahua- the largest ethnic group that speaks Nahuatl

Tenochtitlan- the jungle metropolis in Mexico that had a population between 150,000-300,000 inhabitants

Class Notes, 9/2/19

- Today’s class was guided by three questions: What kind of evidence can we use to analyze pre-Columbus Latin America?, What is material culture and how can we use it as evidence?, and How did the local environment influence civilizations? For the first question, we need to understand that most of the accounts and evidence of the New World are from colonists’ point of views which can be biased and it doesn’t give us both sides of the story. As well as there being potential for ideas and traditions being lost in translation between the indigenous and the colonists. Evidence from pre-Columbus can come from artifacts and excavations, cultural traditions that have survived as well as tribe oral history. We can use surviving texts and inscriptions from the time, as well as the artwork. With modern technology, we can use DNA to look at genetics which can offer us a view of where these peoples ancestors may have come from. We can also use radar and sonar technology to discover lost buildings or sites that have been taken back over by the forest. The next question for class was about material culture. Material culture are the tangibles of a culture, so anything physical, from tools to buildings. For identity, material culture is very important to show what group we belong to, what our status is. The consumption or use of material culture is a way to communicate, without necessarily talking or trying, what your status or class is. Like it was mentioned in class that colonists had strict dress rules with European fashion, this was their showing of class. For the last question, we looked at the environmental influence on societies. Towns and cities were heavily influenced by where they developed by what natural resources were around them. Rivers and lakes were important as they needed a water source for themselves and for irrigation. They also needed areas suitable for growing crops, so areas that get a lot of rain. Deserts were avoided. When colonists arrived, flat land was the hot commodity as they wanted it to grow crops and raise livestock. Indigenous people, however, didn’t always need flat land for agriculture. Take Machu Picchu as an example, they created a city high up in the Andes mountains and were able to create terraces for crops.

- In one of our readings, Mann talks about how traditional scholars and even some new scholars find it ridiculous to claim that there were millions upon millions of Native Americans living in the Americas before Columbus. Some say that there is no evidence for such large civilizations. This relates to our class discussion because we were talking about how evidence is so heavily one-sided towards the colonizers. There is no good estimate of what population sizes were for the Natives that currently survive. The colonizers typically destroyed any written work of the Natives as they saw it as demonic and as a blocker to converting them to catholicism. This is why material cultures other than texts are so important to study these ancient people.

- Key terms:

- material cultures – the physical items and places that are used to represent a culture, can include tools, buildings, artwork, and any other tangible item.

- epidemiology- the study of the patterns and spread of disease through a population.

- More on material cultures of the pre-Columbus Latin American peoples. https://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/9.2/forum_mundy.html

More about different native cultures right before Columbus. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/1492/america.html

The history of animals in Latin America. Although starts way back with mammalian evolution, there is a good section on the pre-Columbian era as well as during the Columbian exchange. https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/abstract/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-436

5. What can material culture tell us about a society that we have very few written record from their point of view or time period? Along the same lines, what can material culture tell us about a civilization that written record can’t?

What kind of evidence would be needed to support the argument that there were millions upon millions of natives living in Latin America pre-Columbus?

KH: I can help you get started with this one, if you’re interested: Koch, et al, “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492“, Quaternary Science Reviews 207 March 2019: 13-36. This starts with a look at multiple different techniques used for estimating population pre-contact. Or for a historian’s look at the impacts of disease, see David Noble Cook’s Born to Die.

Creative thought question: How do you think history would be different if it was the Native Americans that sailed and “discovered” the old world? What would they have thought about Europeans, Africans, and Asians and all of their cultures?

What I’d like to learn this semester

During this semester there are some specific topics I’d like to learn. One of the main ones that interests me is the military conquest of the Europeans and how the natives fought back. Perhaps we’d learn more about particular battles that took place. Clearly the Europeans were at a technological advantage with their firearms, but I’d be interested in knowing how the natives fought back and tried to level the playing field I think that would be very intriguing.

Another main topic I’d like to focus on this semester is religion amongst the natives. Obviously we’ve all seen the glorified human sacrifices on television. I’d like to dive into how accurate and prevalent things such as human sacrifice were amongst natives. Also stuff such as the jaguar being glorified interests me. Was the jaguar and other animals particularly important to native culture or has Hollywood just put more emphasis on these things than actually existed.